Feedback on Fight Back!

For Fight Back! references, news, follow-ups, and to offer your own links, feedback, and suggestions for further reading on the protests, please visit the Fight Back! page, at http://opendemocracy.net/ourkingdom/ourkingdom/fight-back.

http://www.bit.ly/fightbackUK

A Reader on the Winter of Protest

Editor: Dan Hancox

Editorial Kettle: Guy Aitchison, Siraj Datoo, Cailean Gallagher, Laurie Penny, Aaron Peters and Paul Sagar

Published by openDemocracy via

OurKingdom.

openDemocracy

c/oThe Hub

34b York Way

City of London N1 9AB

Mail to:

PO Box 49799

London

WC1X 8XA

email:

[email protected]

URL:

http://opendemocracy.net/ourkingdom/ourkingdom/fight-back

facebook:

http://www.facebook.com/fightbackUK

twitter:

#fightbackUK

@fightbackUK

Published online February 2011

Published in print March 2011

Typesetting and HTML by Felix Cohen.

Set in Hoefler Text and Gill Sans, print versions produced using PrinceXML

Cover designs by Jesse Darling

Everything in this book is

licensed under Creative Commons with a couple of exceptions, used

with the permission of the MSM.

ISBN 978 0 955677 502

Editorial

Kettle

The editorial team were all

kettled by the Police, November-December 2010.

Guy Aitchison is a co-editor of

openDemocracy's UK blog, OurKingdom, and a PhD student in

politics at UCL.

Siraj Datoo is editor of The

Student Journals and reads French with International Studies at

the University of Warwick. He also writes for The Muslim

News.

Cailean Gallagher is

editor-in-chief of the Oxford Left Review and an undergraduate in

philosophy and politics at Oxford University.

Dan Hancox is a freelance

journalist who writes on music, politics and pop culture for The

Guardian, The National, New Statesman and others.

Laurie Penny is a New Statesman

columnist and freelance journalist.

Aaron Peters is a student activist

and is currently reading for a PhD investigating social

movements, collective action issues and the internet at Royal

Holloway University.

Paul Sagar is a PhD candidate at

the University of Cambridge, working on political history and

philosophy. He blogs at Bad Conscience and for Liberal

Conspiracy.

Publishing and Design

Team

Anthony Barnett is a co-editor of

openDemocracy's UK blog, OurKingdom. He was the first director of

Charter 88, helped to found openDemocracy in 2001 and is the

author of various books.

Felix Cohen likes to make things

on paper and the web for nice people. Find him at http://felixcohen.co.uk

Jesse Darling is a journeyman auto-ethnographer and artist of many media: dasein by design and the performance of everyday life. JD lives on the fringes of London and wherever.

Niki Seth-Smith is the publishing Co-Editor of openDemocracy's UK blog OurKingdom; before that she worked for The Statesman in Kolkata and The London Magazine.

Daniel Trilling is an editor at the New Statesman. He writes about politics, music and film - and spends quite a lot of time interfering with things other people have written.

Contents

Note From The Editor

Foreword

A Fight

For The Future

Anthony Barnett, openDemocracy

Overviews

You say

you want a revolution...

Laurie Penny and Rowenna Davies, openDemocracy

From

the Reactive to the Creative

Cailean Gallagher, Oxford Left Review

The

Open-Sourcing of Political Activism: How the internet and

networks help build resistance

Guy Aitchison and Aaron Peters

The Demonstrations

Inside

the Millbank Tower riots

Laurie Penny, New Statesman

The

Significance of Millbank

Guy Aitchison, openDemocracy

I was

held at a student protest for five hours

Sophie Burge, TheSite.org

On

Riots and Kettles, Protests and Violence

Paul Sagar, Bad Conscience

Kettled

In Parliament Square

Siraj Datoo, The Student Journals

Postmodernism in the Streets: the tactics of

protest are changing

Jonathan Moses, openDemocracy

Kettling – an attack on the right to

protest

Oliver Huitson, openDemocracy

The

Occupations

Beyond

The Occupation

Oliver Wainwright, Building Design

At the

Occupation

Joanna Biggs, London Review of Books

30

Hours in the Radical Camera

Genevieve Dawson

Interview with a Royal Holloway anarchist

Asher Goldman, Libcom.org

The

Occupation of Space

Owen Hatherley, openDemocracy

The Flash Mobs

Protest

works. Just look at the proof

Johann Hari, The Independent

The

philosophical significance of UK Uncut

Alan Finlayson ,openDemocracy

'Santa

Glue-In' as 55 Anti-Cuts Protests Hit Tax Dodgers Across The

Country

UK Uncut, Big Society Revenue & Customs

The Universities

Universities in an age of information

abundance

Aaron Peters, openDemocracy

Britain, greet the age of privatised Higher

Education – an argument and a debate

Alan Finlayson and Tony Curzon Price, openDemocracy

Where are the conservatives, as the true history of education goes undefended?

Peter Johnson, openDemocracy

The

Universities should be more inventive than the profit motive

Rosemary Bechler, openDemocracy

I defied the Whips and voted against my government

Trevor Smith, openDemocracy

The Under 19s

The

real nature of the EMA debate

Anthony Painter, Left Foot Forward

EMA

Stories: My Brother, Charlie Martin

Ben Martin

EMA

Stories: An umbilical cord to education

Ben Braithwaite

We are

not the Topshop generation

Anna Mason, UK Uncut

Physically sick

Tasha Bell

The State And Violence

Riotous

Protest – an English tradition

Daniel Trilling, New Statesman

Sharing

The Pain: The emotional politics of austerity and its

opponents

Jeremy Gilbert, New Statesman

The

Media, the police and protest: now both sides of the story can be

reported

Ryan Gallagher, openDemocracy

The

military response to direct action, General Kitson's

manual

Tom Griffin, openDemocracy

Image

of the Year

James Butler, Pierce Penniless

Geographies of the Kettle: Containment,

Spectacle & Counter-Strategy

Rory Rowan, Critical Legal Thinking

The Trade Unions

Unions,

get set for battle

Len McCluskey, The Guardian

Just

what does the Guardian think trade unions are for?

Keith Ewing, openDemocracy

Comment

on Keith Ewing

John Stuttle, openDemocracy

The Aesthetics

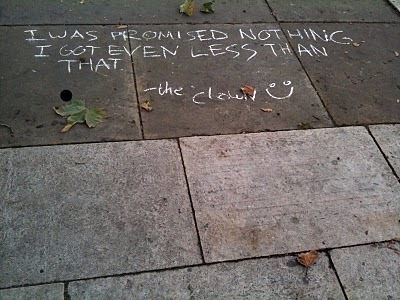

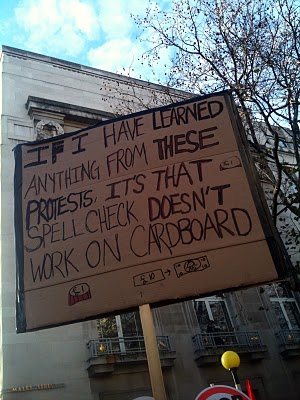

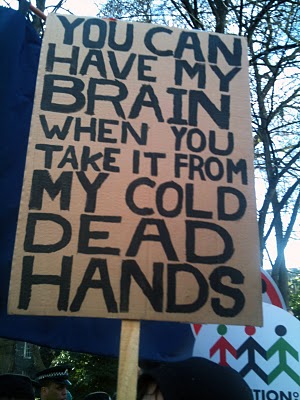

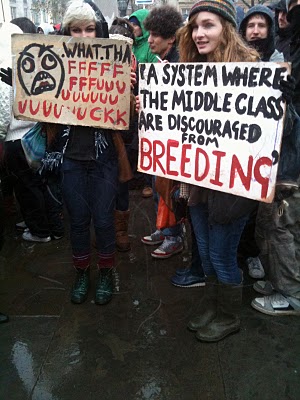

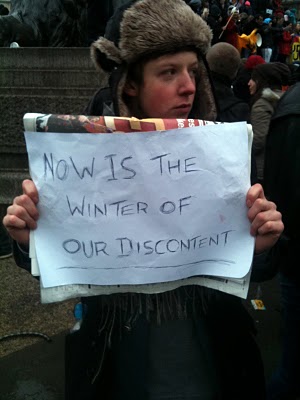

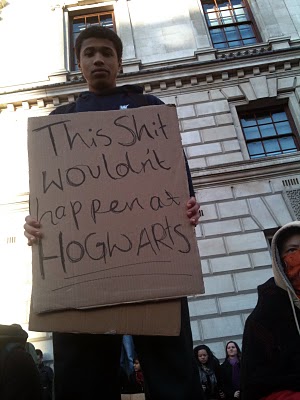

On

[Protest] Signs & the Signified

Jesse Darling, Brave New What

This is

our riot: POW!

Dan Hancox

Images

of Reality and Student Surrealism

Adam Harper, Rouges Foam

The Generations

Will

the ‘Tens’ trump the

‘Sixties’?

Anthony Barnett, New Statesman

The New

Sound of the Streets

Gerry Hassan, The Scotsman

The

Morning After The Fight Before

Nick Pearce, IPPR

Out

with the old politics

Laurie Penny, The Guardian

Is the

students’ conflict intergenerational?

Maeve McKeown, UCL Occupation Blog

Afterwords

Why we

shouldn’t centralise the student movement: protest, tactics

and ways forward

Markus Malarkey, Ceasefire

What

next for the UK's student movement?

Guy Aitchison, openDemocracy

Appendices

Campaigns and Resources

Discussion

Twitter

Green

and Black Bust Card

Third Estate

Sixty Second Legal Check

List

Third Estate

Occupation Cheat Sheet

Third Estate

Note From The Editor

Fight Back! exists because it needs to exist.

If you read the right blogs, follow the right people on Twitter, and subscribe to the

right RSS feeds, then perhaps you've already read most of these articles, during the last few extraordinary weeks of 2010. But what

about the vast numbers of people who don't fall into that group? We have to keep

making noise outside the echo chamber - the potential pitfall of web 2.0 solidarity

networks is that they become a virtual version of the kettle, the sound of our chants

rebounding off the Police lines, forever contained. All of Fight Back's editorial team

have been subjected to kettling by the police during these protests - we know what

it's like in there, and what we're fighting for, and against, and we want to tell people

about it.

This is an opportunity to make sense of the winter eruption, and to take stock: just a small selection of the terrific writing on the protests. Apologies to all whose good material we missed; please visit the Fight Back! page to leave feedback, and offer your own suggestions for further reading. Our aim here is to provide a framework, and to encourage clear thinking, as a guide to the further action we need to take.

But above all, we want to tell the world what happened. I knew something was missing when I called my mother a couple of days after the

#dayx3 demonstration, during which I'd been kettled in Parliament Square for five

hours, and on Westminster Bridge for two hours. She's a veteran of decades of

protests, reads the real-world, papery, inky version of The Guardian every day, and

taught me everything I know. But unlike some of us, she has better things to do with

her time than clicking refresh on the #demo2011 Twitter feed. The point is, she's as

horrified as the most web-savvy student by the public sector cuts, has read everything

about the protests that comes her way - but two days later, still had no idea there had

been a kettle on Westminster Bridge. If her son hadn't personally informed her, she

might still not know there had been a kettle on Westminster Bridge. And who can

blame her, when the official line from the Home Secretary, repeated three times in the

House of Commons, was that it never existed.

So tell a friend - that's how this works. It's how it all works.

#solidarity

Dan Hancox

London, February 2011

Foreword: A Fight For The

Future

Anthony Barnett

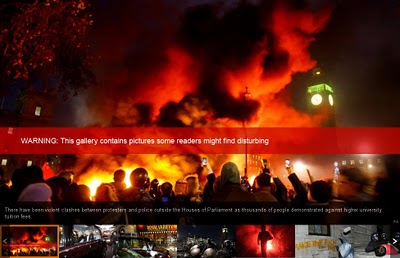

On 10 November 2010 a

student-initiated protest erupted into British politics. It was

followed by an extraordinary month of actions, campaigns, more

demonstrations, civic swarming as well as marches, university and

school occupations, friendly flashmobs that shut stores and

generated media coverage of corporate and individual tax

avoidance, and the storming of Parliament Square on 9 December,

as the House of Commons voted to triple student fees. Thanks to

online networks, over 30,000 turned out in a matter of days when

the government decided to race through the legislation.

Sixteen-year-olds from comprehensives and sixth form colleges in

London's East End joined Cambridge dons and inspired trade

unionists as well as students from all over the UK. The police

responded by trying to trap and then violently kettle as many

protestors as they could. The corporate media sensationalised

acts of vandalism but were unable to caricature the

confrontation, thanks to the social media that dramatised what

really happened. Public support was mixed and took on a life of

its own as polls showed that opposition to the government

increased.

Immediately the web filled with videos, photographs, testimony, blogs,

arguments, twitter exchanges, facebook clusters, posters and

graphic work. The experience of what happened is recorded in many

outlets, told by those to whom it happened and who, more

importantly, made it happen - the activists are also

publishers and co-creators with their own voices. In this reader

you will find just a modest selection but you can follow the

links for much more. What strikes me is the range, good humour

and truthfulness of the young protestors compared to the

confinement and evasions of official politics.

Will these few weeks come to be

seen as the start of a movement that reshapes the wider politics

and culture in our country and shifts the balance of force

between authority and people?

If so the birth was sudden,

forceful, and for some of us bloody. It was also surreal. Prince

Charles, heir to the throne, had

recently declared "I can only,

somehow, imagine that I find myself being born into this position

for a purpose." The purpose, he concludes, is to lead us to

environmental "Harmony", the title of his latest book

published in time for Christmas. It opens with the declaration

"This is a call to revolution". On 9 December he

ordered his chauffeur to drive his Rolls Royce amidst his fellow

revolutionaries. Perhaps he felt that he and his wife would be

greeted as comrades. Instead, they met with the great republican

slogan of high Victorian confidence, albeit originally uttered by

Lewis Carroll's Red Queen, "Off with their

heads!"

A new movement? Round up the usual

gatekeepers! Quite an alliance of forces are darkly jealous of

its potential energy and fresh celebrity - stretching from

News International through the Tory, Labour and Liberal Democrat

parties and goodness knows how many NGOs and bloggers. The

gatekeepers even include those on the far-left who helped it

burst into existence but want to oversee it for themselves. But

this baby, as the readers of this collection can see, is not so

inarticulate or shapeless. Instead, there is a conscious sense of

originality thanks to the power of the modern forces that have

propelled its birth. These give credibility to its double wager

of defiance: that what the state, the government, and the

corporate media offer to the country and especially its young as

our fate is unacceptable, and that the claim which accompanies

it, that there is no viable alternative, is a lie.

Is it possible to have a new

movement baptised by an act of lèse-majestè? Like many a new life

it is needy and inexperienced. It enjoys an inspiring,

protoplasmic will, and a capacity to make noise out of proportion

to its size. And it is vulnerable. It lacks coherence. It could

be snuffed out, or broken by internal differences. But it exists

in a country that since the scandal over parliamentary expenses

in 2009 has clearly needed a new, strong voice of opposition to

the way we are governed, outside official channels.

Now we have one. In a welcoming

spirit of solidarity and kinship, therefore,

openDemocracy's UK section, OurKingdom, is

publishing Fight Back!

- and is learning and being changed in the

process. These days everyone wants immediacy and the first

question being asked is whether the movement will grow. But there

are different kinds of growth and I think the most important

question is whether something new has started that will

last.

I hope you will read this book

with an open mind as the answer is going to be multi-layered. It

depends on the forms of organisation adopted by the protestors,

how links are made with others, on the music and culture that is

being created, and most important on the nature of our epoch and

how open it is to change. The voices of the winter protest can be

judged in terms of naivety or maturity - but what really

matters is the opportunity. Of course there is evidence of

idiocy, over-optimism and simplification as well as the usual

drawbacks of student politics. But the wider anti-cuts protests

that began in late 2010 are not just about fees, and reached well

beyond students - thousands across the country who are not

in higher education are helping to create it. Exceptional

economic, social and technological transformations are underway.

Will this budding movement have the energy, audacity, persistence,

imagination and intelligence to make the best of these

changes?

Losing the future

In the 1980s the socialist

cultural critic and novelist Raymond Williams observed that the

left in all its varieties had lost hope in the future. As

Britain's attempt at social democracy decomposed and the

Soviet bloc stagnated, the left became sclerotic with nostalgia.

At the same time, Conservatives ceased to be backward-looking and

embraced growth and market optimism. New Labour's canny

response under Blair, Brown and Mandelson was to embrace

capitalist globalisation as the replacement of internationalism.

Instead of reinforcing the sense of closure that Williams

diagnosed, this created a countervailing confidence in

'progress' thanks to the expansion of the bubble

economy and the funds it generated for public investment under

New Labour. But its embrace of market fundamentalism proved its

undoing. The bubble of the North Atlantic economies burst in 2008

and in the UK this was closely followed by a political crisis, as

the MPs expenses scandal, itself part of the wider stench of

entitlement and greed, shattered popular belief in the historic

integrity of parliamentarians as a whole.

The electorate judged that no one

party was up to the job of repairing the damage. It voted to hang

parliament in the May 2010 general election. But the Tories

proposed a wholehearted partnership to the Liberal Democrats as a

way out. The resulting Coalition government offered voters an

apparently honest response to the twin financial and political

emergencies, through a combination of principled compromises on

policies and a belt-tightening exercise to secure the economy. It

also committed itself to free the people from New Labour's

overbearing state and its interfering assault on liberty. In this

way, presented as a relatively youthful but not undignified

politics of restoration, the Coalition was widely welcomed. It

turned instead into a two-faced, unprincipled exercise: while

reassuringly Whiggish in appearance, it drove forward market

fundamentalism within the public sector faster and more

ruthlessly than even Blair and certainly Thatcher would have

dared to contemplate, with disregard for traditions and

institutions. At its core is a deficit-reduction strategy that

places support for the bond market, and preserving the City of

London as a base for financial globalisation, above

everything.

This policy is being most

dramatically implemented in higher education. How it came about

is essential background to the protests as it shows how the

issues of fees and how to pay for universities combined from the

start with a much wider philosophy of marketisation that is now

attempting to redefine the very purpose of education

itself.

The Browne Review

In the beginning was the master

manipulator: the yachting companion of George Osborne, New

Labour's Peter Mandelson. Brought back by Gordon Brown to

save his premiership, Mandelson became Secretary of State for

Business, Enterprise and Regulatory Reform in 2008. He then

body-snatched the Department for Innovation, Universities and

Skills to become overlord of the Department of State for

Business, Innovation and Skills. Thus our universities and

hundreds of thousands of students found themselves under the

control of a department that had neither 'education'

nor 'universities' in its self-description. And this

is where they now belong.

Within five months Mandelson

published Higher Ambitions: the future

of universities in a knowledge economy. It praises the expansion of higher education under Labour

and the tremendous investment in British science and advanced

research. It sets out a case for more than half of all young

people having further education, to widen access and raise

standards. There is a touch of pluralism about it too,

"Universities have a vital role in our collective life,

both shaping our communities and how we engage with the rest of

Europe and the wider world". But overwhelmingly it presents

a business case for education as a means to an end, for the

individual and society:

"Higher education equips

people with the skills that globalisation and a knowledge economy

demand, and thereby gives access to many of this country's

best jobs. Everyone, irrespective of background, has a right to a

fair chance to gain those advantages."

To achieve this he opens the way

for increasing fees. Again, in his own words, "It is

necessary to look afresh at the contributions of those who

benefit from higher education the Government will

commission an independent review into this question." This

became the Browne Review.

In a far-sighted assessment of

Mandelson's Higher

Ambitions when it was published in

November 2009,

Alan Finlayson warned that even in

business terms what was needed was the opposite of what it

proposes. Britain should move to a broad, US style, liberal arts

education, says Finlayson, giving an understanding of scientific

methods as well as core principles of history and philosophy,

"to impart skills that a wide range of employers welcome,

and to create citizens conscious of their place in history and

confident about acting in public life".

Alas, Mandelson appoints John

Browne, the disgraced ex-head of BP, to carry forward his work.

The original brief was technical. But if your starting point is

that money is all that counts, you naturally proceed to pass

judgment on everything in these terms. At BP, Browne had

demonstrated a quite exceptional talent to impose his

narrow-minded vision. As

Tom Bower aptly put it, he changed

the company's culture from oil engineering to financial

engineering (opening the way to the recent disaster in the Gulf).

Browne approached universities with the same simple zeal. He saw

them as cost-centres of educational engineering and proposed

turning them into places of - what else? - financial

engineering. Which in this case means making them campuses that

focus on the enhancement of earning power.

His review is published on 12

October 2010, and the government accepts his proposals except

that it caps fees at £9,000 rather than allowing them to be

unlimited. Far from opposing New Labour's inheritance,

which it scorned in public, the Coalition embraces it with

vengeance. In the course of a few days, with the country hardly

aware of what is happening, it is agreed that the totality of the

government's direct public provision for teaching the

humanities (and 80 per cent of all university teaching revenues)

disappears next year. Funding will henceforth be routed through

students in the form of loans. But what is being presented as a

technical answer to a question of payment is in fact a

life-sentence passed on the future generations of

students.

I know of no one who thinks that

universities don't need to be significantly improved or

that there are not genuine questions concerning the future of

higher education, such as raising quality, how to create a system

where everyone can credibly aspire to the jobs they want, the

implications of meritocracy, combining vocational and academic

skills, education being for living as well as employment, and

how the web might open up access.

Browne ignores all this. Higher

education is defined as an investment made by students to enhance

their employment prospects in a corporate world (while

corporations start to take over and run universities for a

profit).

The student's choice is

dressed up as freedom backed by government-secured loans. But

they are obliged to pay to enter what many understandably feel to

be a choiceless world.

I am not exaggerating. Browne

states that there is simply no "objective metric of

quality" available with respect to higher education to

decide how to "distribute funding". Therefore its

money should follow student choice (p25). In order for students

to choose there will be "certified professionals"

appointed to every school, using a "single online

portal" for applications and information (p28). This portal

will:

"allow students to

compare courses on the proportion of students in employment after

one year of completing the course; and average salary after one

year. Employment outcomes will also make a difference to the

charges set by institutions" - its charges will become an

indicator of its ability to deliver - students will only

pay higher charges if there is a proven path to higher

earnings. Courses that deliver improved employability will

prosper; those that make false promises will disappear."

(p28)

The whole of education is

perceived as a means to an end. The possibility that education

might be an end in itself, that it can be dangerous and

liberating, that it might open

up choices and enhance one's

self-development, that it can be life-changing and that society

as well as individuals might wish this to be so, is just about

allowed for in the Mandelson report because it includes vivid

testimony from specific universities. In Browne, the absence of

such possibility is suffocating and complete.

The Coalition's collision

course

By embracing Browne the government

backs his drastically one-dimensional approach. Our response

should not be to deny that instrumental calculations (including

the liability of taking on debt) are part of life, they are; or

that students should not be able to demand a proper education;

they should. What needs to be said loud

and clearly is that the idea that loans to students should be

the only way in which we as a society fund humanities education; that to

survive and prosper universities must think exclusively in market

terms about what jobs they deliver; that our society with all our

history and experience is incapable of agreeing on a mixture of

other ways to recognise "quality" in higher

education, is altogether abhorrent.

That a horrific approach to higher

education is decided and becomes law in a few weeks with no

proper debate or consideration of alternatives suggests a society

whose political system is close to breakdown.

It is not surprising that

ambitious and creative young men and women respond by saying,

'hold on a moment'.

The Coalition's

justification is that swift measures are essential to cut

expenditure and eliminate the deficit over the course of a single

parliament. But Cameron's

underlying desire to privatise the public realm, or as he puts

it, oversee a change from "state power to people

power" (of which his 'Big Society' is a part),

is not a deficit reduction strategy at all. It dates back, he

told the Conservative Party conference on 6 October 2010 -

indeed it is a point he insists on - to well before the

financial crash. He was speaking as the Browne Report was being

prepared for publication. He proclaimed that his government had

begun a "revolution" (its seems quite a popular word

these days amongst the old ruling class) and he boasted,

"We are the radicals now breaking apart the old

system".

It was true, but only for 34

days.

Then his party headquarters at

Millbank by the Thames was stormed.

The pivotal moment of Millbank was

not the smashing of the glass into the entrance, the trashing of

the lobby by the young mob and the triumphant race to the roof by

a relatively small number of exuberant protestors. It was the

larger crowd outside. It was the thousands who cheered them on.

They knew that this would break through the indifference of the

media, that they were making their case in the only way the

spectacle respected, that their anger would be on TV and in the

press. They were cheering something much greater than a protest

over fees.

When they say, 'cut back!'

We say, 'fight back!'

This was the chant that defined

the cause. It is a response to the entire approach of the

Tory-Liberal Democrat Coalition, and not just fees.

The National Union of Students

organised the 10 November demonstration. Later, an informal

network called for another manifestation and after taking to the

streets of London, university occupations began. Enter UKUncut

and False Economy: in parallel with the student protests, they

provided a platform to organise wider protests against the

cuts.

UKUncut initiated enjoyable,

peaceful but unruly flashmobs. On two Saturdays I joined them in

Oxford Street as we temporarily closed high-street chains like

Top Shop, Vodafone and British Home Stores, explaining to

shoppers how these chains were implicated in tax avoidance, with

similar actions taking place in high streets across the

UK.

The web generates a wide number of

weak connections. In contrast, direct actions and especially

occupations can create intense friendships as people collaborate

in open struggle. An experience of agency, of self-determination,

of being an influence, with all the passionate negotiations and

searching for consensus that is bound up with making change,

started to transform demonstrators into activists.

The National Campaign Against Cuts

and the London Student Assembly, working with the occupations,

organised the 9 December march on parliament: over 30,000 sweep

unstoppably on Parliament Square as the most far-reaching single

reform of English higher education is being raced through the

House of Commons, in the form of secondary legislation, incapable

of amendment, in a single three-hour debate. For the first time

in a century, since the suffragettes, a police cordon gets thrown

directly around the Palace of Westminster to protect MPs as they

prepare to vote. Helmeted police with riot shields stretch from

opposite Big Ben to right past the House of Lords as a free

festival of protest takes place in the square itself. By 3.30 in

the afternoon the police vans and horses start to move in, in

full riot gear. Having failed to stop parliament from being

surrounded, they were not going to let it end peacefully, as you

can read in several eyewitness accounts that follow.

From protest to

politics

Student militancy draws on a

variety of sources and experience over the past two decades.

Among them are Reclaim the Streets, Climate Camp, militant

environmentalists, and the demonstrations that marked the meeting

of the G20 in London. These developed techniques of networking,

consensual organisation and activist solidarity. Awareness of the

nature of the surveillance society and its policing techniques

was dramatised by the Convention on Modern Liberty in 2009

(supported by 50 organisations, among them The Guardian,

openDemocracy and the activist network NO2ID; Henry Porter and

myself were co-directors). The far-left maintained a steady

organising presence. A lively left blogosphere, full of ideas and

with a focus on action and solidarity, began under New Labour and

was stirred up by the general election in May, encouraged by

group blogs like Liberal Conspiracy and The Third

Estate.

Then there are the Liberal

Democrats. They had recruited among students as part of the

growing opposition to the two main parties. They preached that

politicians had lost the trust of young people but that

they were the

solution as they alone could actually win seats and stay honest

and be trusted. With the student vote increasingly important in

university towns where the Lib Dems did well, they had gone out

of their way to pledge in writing that they would not support any

increase in fees. They did not just 'break' this

promise. It was a betrayal - creating intense anger because

they had recruited on the even more important promise that they

were different and would do no such thing.

From dramatic high-risk forms of

resistance to tactical voting for Clegg and his party, all these

actions, conferences and reactions, were protests. By contrast, the

experience recorded in these pages suggests that the "fight

back" of winter 2010 contains the seeds of a

politics.

Here is why:

- The protest movement

born in the winter of 2010 is directed at the totality of the

government's economic policy and therefore engages with

the state's management of democracy and power. At the

same time the government's attempt to save market

fundamentalism means preserving an unparalleled degree of

inequality in terms of top salaries and bonuses. This

super-inequality has lost all public credibility since the

crash. Market fundamentalism is losing political legitimacy, a

profound shift that opens up a space for far-reaching

challenges to thrive.

- One of the drivers of the

crisis has been capitalism's capacity for productive

transformation as well as financial bubbles, in this case the

upturning of productivity thanks to the microchip and the

internet. Student occupiers had more computing power in their

laps than NASA when it sent Armstrong to the moon. Social

networking is already transforming the way social decisions are

being taken, which is itself a definition of

politics.

- A politics without a culture is

merely technocratic. But we are at the forefront of an immense

cultural transformation - not necessarily positive, but

that's the point, a complex confrontation is underway.

This applies especially to what it means to be educated and

therefore cultured. It goes much further than working class

access and costs. The principles of the Enlightenment, from

human rights to the influence of religious belief, are in

play.

- The Westminster system has

entered an endgame. Higher education has been swept into the

department of business; the Browne proposals have become law;

all this and much more has been driven through without a proper

debate in the Commons, let alone pre-legislative scrutiny and

the chance to propose alternatives. There is little meaningful

democracy, the 'sovereignty of parliament' is a

joke, reliable checks and balances have ceased to exist in the

UK: the executive rules and the constitution is broken. Hence

the need to riot.

A political process that is losing

consent; an economic order whose inequalities have undermined its

legitimacy; the arrival of new ways of organising power and

influence thanks to technology and social media; taken together

such a combination makes it possible for an influential

democratic movement to emerge - one which does have a

belief in the future.

The new Levellers

Nationally, however, the right is

still in the ascendency and internationally it is ascendant. It

too is using new technology for its ends and is debating how

democracy and the economy should be organised in its interests,

in an era when the traditional political party is in advanced

decomposition. That the internet will indeed change things deeply

is for certain, how it will do so is not

pre-determined.

So this is quite a dangerous

moment for the movement if it is to grow, and evolve, and become

more than a protest.

The first demonstration of 2011: a

symbol of parliament itself, a 20 foot high effigy of Big

Ben,

is burnt on 2 January. It takes place

far from crowded streets in a clearing within the historic Royal

Forest of Dean. Local people are determined to protect their

forest from being sold off into commercial hands. This poses an

issue that haunts British politics - the UK's

national question. Should the Coalition insist on its plan to

sell off our woodlands, can the cities link arms with the

countryside to overcome one of the most crippling divisions in

English democracy?

The Coalition's decision to

abolish the EMA, the Educational Maintenance Allowance for 16-19

year olds from poorer and very poor households, created furious

opposition in schools and sixth-form colleges with a high

proportion of working class children. Many joined the

demonstrations which, from the start, were not confined to

'privileged' students of whom there are anyway over a

million. Cross-class solidarity was built into the DNA of the

movement against the cuts from the start, while trade unions

leaders, as these pages record, welcome it.

On 8 January the TUC helped host a

meeting of NetrootsUK

at Congress House. Perhaps only 10 per cent of

the 500 online activists who attend are trade union organisers,

but in terms of the British labour movement it is an exceptional

exercise in openness and shows a remarkable lack of tribalism.

The TUC has called for a massive demonstration on 26 March. This

is likely to be supported by local councils who hate being forced

to implement cuts, as well as many from across the NHS now

undergoing its own radical marketisation. It is very early days,

but the students may be initiating a social movement that addresses

the larger interest of society.

Members of political parties are

sniffy, while Labour ones claim that it is they who should speak

for any new opposition. Certainly, they badly need more energy.

But one of the inspiring aspects of the protest movement is its

sensitivity to process. It is not whether Labour or the Greens of

the Scottish or Welsh nationalists support this or that policy on

education or the cuts that will count, but how they do so. Can Labour open

up to the widening force of the anti-cuts movement so that it is

changed by it? It may then have a chance not just of being

re-elected but also of governing better when in

office.

The Coalition's

"revolution" will make Britain a safe haven for

international finance and corporations in the hope that they will

ensure domestic economic growth from above. But what kind of

economic development and self-government will the opposition to

this fate propose in its place? The Coalition is busy modernising

parliament: equalising constituency sizes, reducing the number of

MPs, replacing the House of Lords, while reinforcing the

exceptional power of the executive over the Union. What

counter-programme of democratic reform and what kind of state is

needed to enhance our democracy now that a return to the status

quo seems impossible?

Amongst the students the debate is

more radical despite the danger of looking inwards. Two broad

approaches are engaged in what can very roughly be described as

an argument between two traditions, that of Lenin and that of the

Levellers. Leninism distrusts participation and engagement,

fearing it will become contamination (unless it is disciplined by

'entrism,' or other forms of undercover activity). It

seeks polarisation while it waits for the larger crisis and total

insurrection. My own preference is for the Leveller tradition,

which is altogether more open. Many of the current

movement's egalitarian hopes are familiar and none the

worse for that. They go back to our Civil War when the first

modern call for political equality went out, "The poorest

He that is in England hath a life to live as the greatest

He". It is a tradition that threads through the works of

William Blake, Tom Paine and Shelley and the spirit of the

suffragettes and it has awoken from hibernation. It is inventive,

humane as well as radical, engages with the economic and

political forces around it and calls for liberty and

rights.

New technology has the potential

to empower this 'Leveller tradition' of radical

self-determination. One of the themes

running through these pages is a feeling that the profound

socio-economic changes and the collapsing costs of communication

have made it possible to achieve a modern livelihood through

mutual ownership, economic optimisation rather than maximisation

and co-creation (and creative commons copyright under which this

collection is published). Ironically, those who want to limit the

marketisation of everything are starting to enjoy the

technological capacity to do this, thanks to the immensely

productive expansion of capitalism.

Perhaps another way of registering

how genuinely radical the historic moment is, is by asking who

are the conservatives and who are the extremists?

Are the conservatives really the

Etonians who want us to buckle down to globalisation as they sell

off the forests, tender NHS provision to US for-profit health

providers, marketise education and give parliament a good

slapping? Are these the traditionalists?

Are the extremists really those

who want to preserve the status of the forests, ensure that those

who run the NHS believe in it as a public service, see education

as about developing our human capacities, practical as well as

intellectual, and call for pluralism and mutual respect? Are

these the revolutionaries?

We were supposed to sit back and

admire the Prime Minister and his deputy, as they displayed their

radicalism on our behalf. The police were doubtless prepared for

small numbers of objectors. Now, both in fact and metaphorically,

an effort is underway to corral the unexpectedly numerous

expressions of resistance and throttle them. Our

'leaders' would prefer to close down the attitudes,

ideas and militancy of the winter protests evident in

Fight Back! They want

to ensure that the energy, intelligence and inventiveness are

contained, that its thinkers, artists, bloggers and activists

squabble, divide, are rendered harmless and do not develop a

politics which lasts or ideas that are of any influence. The

book's editorial flashmob have all literally been kettled

by the police. I feel that they are not going to be successfully

confined. But a much larger exercise is underway to kettle the

spirit and creativity of the potential movement against the cuts

and market fundamentalism, so as to isolate it from society. We

must do everything we can to make sure that it remains open and

free to grow.

You say you want a

revolution...

Laurie Penny and

Rowenna Davies

openDemocracy

How to believe in change? This

exchange was published in July 2010 but it prefigures the energy

and issues released by the protests that erupted in November and

December, and expresses the frustrations that were building up

well before the Conservative-Liberal Democrat government

announced its plans for higher education.

Laurie Penny:

Not every generation gets the

politics it deserves. When baby boomer journalists and

politicians talk about engaging with youth politics, what they

generally mean is engaging with a caucus of energetic, compliant

under-25s who are willing to give their time for free to causes

led by grown-ups.

Now more than ever, the young

people of Britain need to believe ourselves more than acolytes to

the staid, boring liberalism of previous generations. We need to

begin to formulate an agenda of our own.

There can be no question that the

conditions are right for a youth movement. The young people of

Britain are suffering brutal, insulting socio-economic

oppression. There are over a million young people of working

age

not in education, employment or training, which is a polite way of saying "up shit creek without a

giro".

Politicians jostle for the most

punishing position on welfare reform as millions of us languish

on state benefits incomparably less generous than those our

parents were able to claim in their summer holidays. Where the

baby boomers enjoyed unparalleled social mobility, many of us are

finding that the opposite is the case, as we are shut out of the

housing market and required to scrabble, sweat and indebt

ourselves for a dwindling number of degrees barely worth the

paper they're written on, with the grim promise of spending the

rest of our lives paying for an economic crisis not of our making

in a world that's increasingly on fire.

Just weeks ago, as news came in

that the top 10 per cent of earners were getting richer,

21-year-old jobseeker

Vicki Harrison took her own life after receiving her 200th rejection slip. Whether a youth

movement is appropriate is no longer the question. The question

is, why are we not already filling the streets in protest? Where

is our anger? Where is our sense of outrage?

There are protest movements, of

course. It would be surprising if anyone reading this blog had

not been involved, at some point over the past six months, in a

demonstration, an online petition or a donation drive. We do not

lack energy, or the desire for change, and if there's one thing

that's true of my generation it is our willingness to work

extremely hard even when the possibility of reward is abstract

and abstruse.

What we are missing is a sense of

political totality. From environmental activism to the recent

protests over the

closure of Middlesex University's philosophy

department, our protest movements are

atomised and fragmented, and too often we focus on fighting for

or against individual reforms.

We need to have the courage to see

all of our personal battlegrounds - for jobs, housing,

education, welfare, digital rights, the environment - as

part of a sustained and coherent movement, not just for reform,

but for revolution.

For people my age, growing up

after the end of the cold war, we have no coherent sense of the

possibility of alternatives to neoliberal politics. The

philosopher

Slavoj Zizek observed that for young

people today, it is easier to imagine the end of the world than

the end of capitalism.

For us, revolution is a retro

concept whose proper use is to sell albums, t-shirts and tickets

to hipster discos, rather than a serious political

argument.

Many of us openly or privately

believe that change can only happen gradually, incrementally,

that we can only respond to neoliberal reforms as and when they

occur. Youth politics in Britain today is tragically atomised and

lacks ideological direction. We urgently need to entertain the

notion that another politics is possible, a type of politics that

organises collectively to demand the systemic change we

crave.

Revolutionary politics involve

risk. Revolutionary politics do not involve waiting patiently for

adults to make the changes. They do not come from interning at a

think tank or opening letters for an MP, and I say this as

someone who has done both. Revolutionary politics are different

from work experience, and they are unlikely to look good on our

CVs.

The young British left has already

waited too long and too politely for politicians, political

parties and business owners from previous generations to give

space to our agenda. We have canvassed for them, distributed

their leaflets, worked on their websites, updated their twitter

feeds, hashtagged their leadership campaigns, done their

photocopying and made their tea, pining all the while for

political transcendence. No more; I say no more.

A radical youth movement requires

direct action, it will require risk taking, and it will require

central, independent organisation. It will not require us to join

the communist party or wear a silly hat, but it will require us

to risk upsetting, in no particular order, our parents, our

future employers, the party machine, and quite possibly the

police.

The lost generation has wasted too

much time waiting to be found. Through no fault of our own, our

generation carries a huge burden of social and financial debt,

but we have already wasted too much time counting up what we owe.

It's time to start asking instead what the baby boomer generation

owes us, and how we can take it back.

No more asking nicely. It's time

to get organised, and it's time to get angry.

Laurie

Rowenna Davies:

Laurie,

You paint a vivid picture of a

young, struggling underclass being exploited by adults, and

it's obvious your cry for revolution comes straight from

the heart. But do we really want to make age another battleground

in our communities? As members of the left, don't we

believe that the real divides in our society aren't between

young and old, but between the rich and poor, the powerful and

the vulnerable? Do we really have space for another

division?

As a true believer in progressive

politics (and at 25, perhaps still a young person), I believe we

should be allying ourselves with all those who feel oppression,

not just those of a similar demographic. The alternative is to

risk segregating ourselves into another youth playpen,

disconnected from the left's mainstream movement.

Let's fight for the bigger picture, not a youthful

self-portrait.

It's a common mistake of

adults to assume that because we're young, we all think and

feel the same. Sure, young people tend to feel injustice

particularly sharply as a demographic because we all start at the

bottom of the jobs pile. But that doesn't mean that all

young people are powerless to the whims of adults. Conservative

headquarters are filled with fresh-faced young graduates that are

working on policies that screw over people old enough to be their

parents and grandparents. How does a "youth movement"

deal with that?

Nor do I agree with your vision of

revolution, as beautiful as it sounds. Bringing this system to

collapse would result in massive economic instability that would

undermine the employment chances of all people - young and

old. It would fly in the face of the last democratic vote and

threaten the social stability of our communities.

So what's my alternative?

Your passionate eloquence leaves my response vulnerable to

looking like a tired defence of the status quo. But I share your

fierce urgency for change - I just don't want to see

young people tearing down the system. Instead I want to see us

enter it, take charge and reshape it. I want to see us filling

the youth wings of our political parties and demanding they give

us more power, as

Young Labour is already doing.

One

initiative I'm pushing for helps to get young people into local government, not as

token youth reps or pen pushers or photocopiers - but as

legitimate representatives of their communities.

In short, I want to see a

generation that fights for each other rather than on the streets.

A youth movement that stands by fellow interns, refuses to work

without pay and raises the temperature on educational funding.

Yes this will take direct action and organised protest. And yes

our targets will often be 'youth issues' - but

they should always be part of a bigger picture, as the students

and lecturers who stood together at Middlesex will tell

you.

I can understand your frustration.

After thirteen years of a 'progressive government',

we are still told that we can't afford to pay for

internships, let alone redress substantial inequalities. But we

mustn't underestimate the difference that policy can make,

as this Conservative budget is about to prove.

I agree with so much of your

clear-spirited diagnosis of the problems. It's your

solutions I'm questioning. Are you completely disillusioned

by the system? Is there really no hope for change from within?

And if not, why do you keep voting in our elections, and urging

others to do the same? Can political parties help turn things

around, or might they just as well disband? I'd like to

know how you think the system should change to make young people

like yourself believe in it again.

Row

Laurie Penny:

Row,

You asked if there isn't hope that

young people can change the system from within. The short answer

is: none at all, if that's all we're planning on doing. For too

many people our age, political activism is just something that

looks good on our CVs, something that involves photocopying,

distributing leaflets and answering the telephone for adult

politicians whose agendas we may not necessarily agree with

- often for free.

We worry, and rightly so, about

being shunned by the establishment, when really we should be

trying to impose our own values upon it. Fortunately, that

doesn't necessarily have to involve pepper spray and water

cannon. You say that you want to see "a youth movement that

stands by fellow interns, refuses to work without pay and raises

the temperature on educational funding... direct action and

organised protest." in my book, that's the very definition of

revolution. Revolution is about challenging hierarchies of

labour, property and power; it's not just about slogans and

terrible hair, and sometimes revolution can work in the gentlest

of ways.

You say that a call for young

people to rebel poses a risk of further division in our

communities, but I firmly believe that generational politics and

the politics of class and capital should not be mutually

exclusive. Young people in particular need to understand that our

place in the hierarchy of labour and property is lowly, insecure

and unjust, and only by developing a sense of solidarity and real

rage will we begin to approach that understanding

appropriately.

My greatest fear for our

generation is that we will grow up to inherit a poorer, harsher,

more difficult world than our parents without once having

mustered the courage to question what brought us to this

point.

Even before the financial crash,

most of us who grew up through New Labour's exacting

reforms to secondary and higher education have been conditioned

from an early age to see ourselves as little more than commodity

inputs. Now, with wages low, job security non-existent and

seventy of us competing for every vacancy, there is a danger that

we will feel too frightened of being left behind by the market to

demand our rights to work, housing, a decent standard of living

and a sense of security that means more than a neoliberal

soundbite. We have been trained to compete, and to see one

another as competitors, and this too is a reason to cherish

revolutionary spirit.

What do I mean by revolution? Not

blood in the streets, although direct action must be a part of

any movement. Not just anger: raging at the baby boomers

won't solve any of our problems by itself. Deep ideological

questions of class, equality and the nature of late capitalism

will continue to matter to people our age long after we have

buried our parents and taken on the work of running the country.

If we are to stand a chance of doing so with any semblance of

maturity and responsibility, we need to remember what it's like

to believe in change, change that's not a slogan on a poster or a

platitude from a pundit but a concrete plan to improve our lives

collectively.

That's why I'm quite

serious in calling for revolutionary sentiment. We need to

understand how badly we have been let down by the system, because

one day we are going to be in charge of that system. People don't

truly treasure things until they've fought for them, and it's

only by fighting for political emancipation, equality and social

justice that we'll be able to pass those things on to generations

who will come after us. If we truly mean to create a decent

society for ourselves to inherit, we need to risk upsetting

people. We need to risk being badly behaved, and making ourselves

less, rather than more, employable. To do politics properly, we

need to risk getting in trouble.

Laurie

This exchange was originally

published on openDemocracy.net, 30 July 2010

http://www.opendemocracy.net/ourkingdom/laurie-penny-rowenna-davies/you-say-you-want-revolution

From the Reactive to

the Creative

Cailean

Gallagher

Oxford Left Review

The power of student activism and

mass action is growing. The cuts are radicalising people,

resulting in waves of protests at local and national level. We

are witnessing, and participating in, the development of a new

political culture, but there is a danger the passion may burn

itself out if it is not focused and directed. Meanwhile, the

principles of the student demonstrations - fair and free

education, available to all; opposition to education and

public-sector cuts; and the right to express a democratic will

- are all principles of the left. This represents a chance

and a challenge for the left, and we must use this opportunity to

renew our ideology, and to combine it with a new culture of

creative activism.

Beyond the Cuts

'Tory scum! Tory

Scum!', 'No ifs, no buts' - the

reactionism of the protests is justified, at least initially, and

is an important part of mobilising and inspiring people to fight

against the cuts. Yet this is simply the beginning. To avoid

impotence we have to go further; we need to develop creative,

radical alternatives for our movement, developed on our own

terms.

The right have tried to frame the

debate so that there appears to be no alternative. We - the

left - need to stop merely responding to the arguments of

the right within the narrow parameters of debate set by them. It

is Advantage Right if, instead of saying 'don't make

cuts', we are forced to say 'don't make

cuts there'.

All the tricks are being used to

limit attention to the scale of their reforms. First, each policy

announcement is expressed in terms of consensus and progress

- this word 'progress' has lost its meaning,

just as the word 'society' has been hijacked. Second,

they are using the old technique of making things which are

constituted by social relations - such as the economic

crisis - appear external and thus 'out of our

control'. This allows them to defend the preposterous

notion of needing to run Britain like a business and to transform

the 'services' it 'provides', so as to be

efficient, preference-based and subject to competition. The

effect of this is to reduce, or nullify, the 'critical

space' within which people might engage in debate; the only

space where debate seems possible, sensible or worthwhile appears

to be that framed by the right.

The narrow debate is evidenced in

the feeble response of the parties of the 'broad

left' which, seeking to occupy the consensual

centre-ground, have adopted and adapted to the neoliberal

ideology. It falls, then, to others to make people aware of the

scale of the cuts - and to resist the hegemonic claim that

they are necessary - and also to make people aware of the

government's total agenda. The whole culture of the future,

as well as the welfare of the people, is at stake. This is a

tipping point; this is the one opportunity to resist changes to

culture, education, public services and society that, once made,

will be near impossible to reverse.

But it is also essential to move

beyond this resistance and reaction, and to use the opportunity

for ideological renewal - attacking not just the

Tories' agenda, but the whole structure of society, with

assertive ideological language; heeding the experience of other

countries; not just drawing on past history, as the Left is so

prone to do, but generating new ideas of culture, education,

society.

The Left has to unite, not as a

monolithic entity (and certainly not within the stubborn populism

of a party machine), but as a creative force challenging the

incumbent orthodoxy. We need to establish what we are fighting

against, and to build a broad, dynamic movement, which can both

mobilize and generate ideas. There need to be imaginative

alternatives. The bystander-culture of the intellectual and

student classes needs to change; this renewal needs the

involvement and contribution of those who would normally sit and

watch.

The role of students

Students must be, and already are,

an essential part of this renewal. There are practical reasons

for this: we are well-placed to protest and organize. We have the

energy and time to act again and again, and to keep struggling;

we can be creative in our methods of dissent, we can communicate

and organise faster than ever before, and we can commit in a way

that no others can. We aren't just marching for our own

sake; we won't have to pay the higher fees. But we will

have to live in the society that is being created now.

We have the access to the

literature, ideas, and minds we need to generate an ideology and

culture for the society we want to live in. As students we occupy

a privileged position within the existing elitist academic

structures. Members of an elite can use their position to the

advantage of society as a whole. When we write and organize, our

methods and language will be drawn, inevitably, from our studies,

but we will be deploying them for our own radical ends. We need

to read, write, talk, experiment, so that we can understand both

what we learn and what we are trying to achieve.

The student movement is unique in

that it has the power to marry activism and ideology. As students

we can use our privilege to develop new ideas for the Left; and

then can practice what we preach.

In Oxford dozens of students

occupied the iconic Radcliffe Camera with the stated aim of

making information and knowledge public and free to all -

as expressed in the statement that the fortress of exclusive

learning is "now a public library". During the

occupation, plans were made to photo copy university books for

public access, before the police forced entry and evicted the

occupiers. And the following week, a 'Free School'

was held in Oxford, where tutors, students, members of the public

and police were all involved in educational sessions. Oxford is a

city defined by its walls, its collegiate enclaves. The campaign

in Oxford fights the cuts in whatever way it can, but it also

combines ideology with activism to pursue the ideal of making

Oxford a city defined by free, open, universal education. No

walls, no exclusion, no fees.

The potential

So the work of this student

movement can go far beyond the reactive, and even beyond the

conventionally 'political'. We can in our actions

begin the fight for the real benefits of free education: not just

free to access but free from the limitations imposed by the

academic system. Free education can expose and analyse knowledge

and ideas that find no place in tutorials, lectures and classes.

Vitally, it can foster innovation in methods and ideals of

collaborative education - open, flexible, critical,

creative - that must have a central place in the

left's vision of education and society. Students and the

public are not only being exposed to new thought, and making

connections between different ideas; they are creating new ways

to envision learning itself. These alternative forms of education

will in turn generate more alternatives, and release more

creativity.

There are other benefits. The

unquantifiable benefit of an enthused young person, who had

previously considered herself un-interested and un-interesting,

being exposed to new and exciting ideas. The tangible benefit to

the social fabric resulting from the general feeling of universal

access to previously privileged knowledge. The restoration of a

pedagogical stance towards the value and purpose of education:

knowledge for knowledge's sake, and knowledge for the sake

of self-knowledge.

If the student movement moves from

the reactive to the creative, it can promote the re-invigoration

of an emaciated British intellectual culture, and the development

of a new 'critical space' where orthodoxies are

challenged. This is a necessary prerequisite of renewed

ideological salvos on the part of the Left.

The anti-intellectualism of the

post-Thatcher political landscape was the necessary corollary of

the anti-ideological stance of neo-liberalism in general. It is

often suggested that knowledge only exists for the sake of

economic benefit (a la the Browne Review, or

Mandelson's Higher

Ambitions, November 2009), or for its own

sake entirely alone. What is overlooked is that in being

considered an end in itself, education serves greater ends as an

indirect result, through generating new ideas for culture,

economy, society. The role of students is to make this message

heard by politicians, but also to demonstrate it through creative

action.

We turn to knowledge and learning

with activism in mind, and bring a new language and ideology to

this critical space. This is done for the sake of an end we

believe in that is not expressed in society - of free

universal access to education. In the process, this will give us

the tools to challenge the hegemony of the right. Through its key

role in ideology and activism, and the growth that comes through

their synthesis, the student movement has the potential to be a

powerful element in the renewal of the Left. We have a duty to

take up the challenge.

This article was written in

collaboration with other editors of the Oxford Left Review, and

is adapted from the the editorial of the November 2010 issue. The

Oxford Left Review can be downloaded for free at

http://www.oxfordleftreview.wordpress.com

The Open-Sourcing of

Political Activism: How the internet and networks help build

resistance

Guy Aitchison and Aaron

Peters

It has been an exhilarating

experience being part of the extraordinary outpouring of student

energy and activism over the last few months. Although we may

have lost the vote on tuition fees, we won the argument about the

role of higher education and blew the political space wide open.

In the process, two cherished myths within official debate, vital

to the Coalition's sense of self-confidence and purpose as

it goes about dismantling the post-war social democratic

settlement, have been demolished. The first was the notion,

reinforced by an obliging media, that Britain has a largely

passive and quiescent population who, unlike their continental

counter-parts, can be relied upon to meekly accept the fate

handed down to them, with the young especially dismissed as lazy,

feckless and self-interested.

The second governing myth, lying

in tatters, is that the government's economic agenda is in

any way "progressive" and concerned with

"fairness". David Cameron had attempted to distance

himself from his bellicose predecessor Margaret Thatcher,

dressing up the Coalition's anti-state agenda in the fluffy

rhetorical garb of the "Big Society" with its

emphasis on devolving power, voluntarism and self-help. This

lacked plausibility at the best of times, and can now be seen for

the sham it is. Six months into the Coalition and groups of

students and children have been repeatedly kettled, beaten and

horse-charged outside Parliament with the BBC's chief

political correspondent, Nick Robinson, declaring that government

has "lost control of the streets". Civil society has

rejected the role allotted to it by Tory spin doctors, instead

meeting and organising in opposition to the government's

austerity programmes.

Taking part in the UCL occupation,

and participating in other student meetings and occupations, it

was striking the number of trade unionists who said they had been

inspired and energised by the spirit and determination of the

students. Encouragingly, this sentiment now finds echoes amongst

the union leadership with Len McCluskey, the leader of Unite,

calling for trade unions to join forces with the

"magnificent

students' movement" (see

section 7). This call, from the leader of the country's

biggest trade union, would have been unimaginable during earlier

periods of union militancy in the 1970s and '80s and

presents a historic opportunity for the left. If it is to defeat

the rampant forces of market fundamentalism to achieve a society

based on justice and equality then obsessing over the

machinations of Westminster village, and the political stance of

the Labour leader Ed Miliband, will not help. Parliamentary

representation matters, but it is by orientating itself towards

the public, rather than party leaders, that a movement gains

influence.

For us, the key question now is

how to turn rhetorical expressions of solidarity into concrete

and lasting relationships of support and co-operation and how

disparate campaigning groups - some local, some sectoral,

each with their own battles, but united in opposition to the cuts

- can link up to defeat the Tory-Lib Dem plans. One key

consideration is how the movement can maintain its forwards

momentum and militancy and not get sucked into a drawn out game

of waiting for institutions hidebound by conservative

leaderships.

This reader on the winter protests

brings together just a small sample of the many reports and

accounts of what happened in November and December. They are

followed by examples from the wider arguments - over the

government's policy on higher education; policing and the

barbaric use of kettling; the contribution of trade unions; the

question of generational change. Already, another

'reader' of similar length could be put together from

just the blog posts debating the organisation of the movement as

a wide-ranging argument developed between

those who emphasise the power of networks to release the

creativity and self-organising power of activists and those who

stress the effectiveness of central organisation and

democratically accountable leadership.

As our contribution to the

overviews, we want to set out how we think the originality and

energy of what has happened can be best maintained in the context

of the epochal transformation now underway.

To simplify, those who back the

power of networks are content for the

movement to remain precisely that, a social movement, held

together by on and offline networks, and formulating a shared

identity and set of political goals in an organic process of

bottom-up deliberation. Whereas those who want central

organisation and leadership wish to see

the establishment of a Social Movement Organisation, formalized

in stance, procedure and practice that is subject to theoretical

homogeneity and the diktat of a centralised leadership and

bureaucracy. Drawing upon popular conceptions about what is the

most "natural" way to organise human affairs, they

argue for the effectiveness of hierarchy, a form of organisation

which is any case inescapable, as de facto leaderships emerge in

a process described by Robert Michels at the beginning of the

20th century as the "iron

law of oligarchy".

Of course, the choice is not as

polarised as this and it would be foolish for anyone to argue for

a single exclusive model in campaigning against the cuts. If we

are to see the emergence of a broad-based popular movement,

uniting everyone from young social media enthusiasts to OAPs,

then there will need to be a patchwork of different campaign

groups across different sectors of society, some with elected

leaderships and others without, each with their own methods of

organisation and communication. Activists concerned with

galvanizing popular resistance to the cuts will need to engage in

what will inevitably be a slow and painstaking process of working

with established institutions, not least the trade unions, and

convincing them to take action.

At the same time this should not

blind us to the fact that some of the most promising action in

the anti-cuts movement so far has been a result of the challenge,

by networks, to the monopoly traditional institutions have

historically enjoyed over information and social co-ordination.

The terrain of collective action is being transformed and this

has opened up the exciting possibility of a powerful and rapidly

growing mass movement beyond the capacity of regulation of any

central leadership. The ideas on which such a movement could be

based certainly aren't new. The long and complex history of

the mutual aid tradition of anarchism has demonstrated the

co-ordinating capacity of networks based on equality,

participation, and self-organisation. Indeed, in practicing

consensual democracy, the occupations and other sites of student

resistance, are self-consciously working with an anarchist

tradition based around autonomy and an ethos of co-operation and

communality. What is distinctive about the current situation is

that the amplification of the vital role networks can make in

mobilising resistance by the "open

sourcing" of political

activism. For the first time in human history we have the

possibility to organise on a dramatic scale without monolithic

organisations. With the technological revolution in networks and

the internet, collective action just got a whole lot

easier.

The 'open sourcing'

of political activism

Historically understood, social

movement organisations have exhibited organisational

characteristics similar to what Erik S Raymond describes, in the

context of software programming, as 'Cathedrals',

the closed-source cathedral model being one in which

"source code is available with each software release, but

code developed between releases is restricted to an exclusive

group of software developers".

The cathedral model was determined

by the technologies available: the assembly line, a centralised

management structure, a rigid and hierarchical division of

labour, and forms of mass communication premised on the

"one-to-many" model, such as newspapers, radio and

television. These had a tendency to favour established elites and

were prone to obsolete ways of thinking and problem-solving over

risk taking and innovation.

The Cathedral model has informed

the attributes of organisations in the political, commercial and